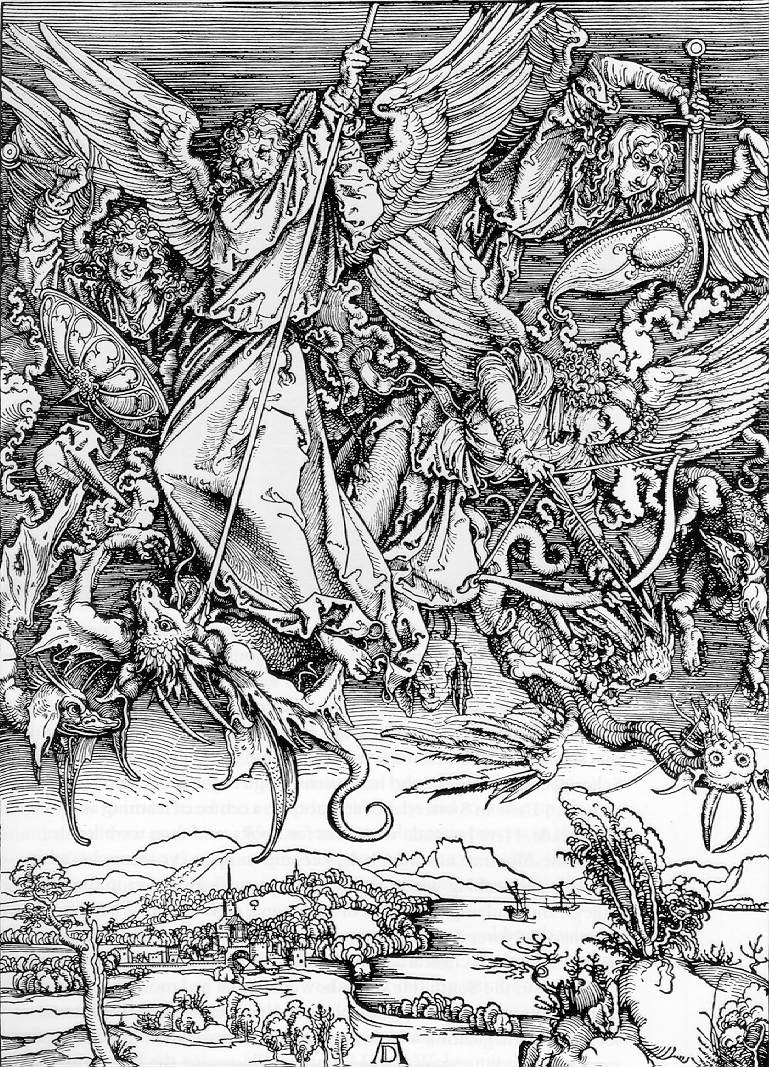

After dinner on Friday, the Bach Festival makes a switch from the intimacy of a small instrumental group and choir, to the grandeur of some of Bach’s most epic cantatas, with full choir, a big orchestra (relative to Bach’s time) with trumpets and drums. Though, as you’ll soon see, some of these cantatas also have some of the most sublime arias in very intimate settings. We begin the Friday evening program with one of Bach’s Michaelmas cantatas, composed for the Feast of St. Michael and All Angels. I wonder if Bach had seen Albrecht Dürer’s infamous woodcut of St. Michael, because something deeply triggered Bach’s creative juices in the pieces written for this occasion. Perhaps the mildest is Cantata 149, “There Are Joyful Songs of Victory,” but it’s still quite a hoot, with some of Bach’s most cheerful writing for bassoon obbligato. Then there’s the matter of Cantata 130, “Lord God, We All Praise You,” with it’s exceedingly exuberant whirling and churning opening chorus, and a three trumpet and drums depiction of a battle with a biblical dragon. Well familiar with those two cantatas, I hadn’t known Cantata 19 until it arrived in the mail on a recording from John Eliot Gardiner’s Bach Cantata Pilgrimage of 2000. I cued it up on the hi-fi, and heard the opening notes of a melisma in a solo line for the choral basses. “Interesting,” I thought. The melisma continued, as other parts came swooping in, and when all four voices of the texture were flitting about, in came the brass and timpani, all dancing away in an extremely fleet meter of six. “What the heck is that?” I thought. I listened to the contrasting B section, with stressed words “RAssen,” “SCHLAngen,” “HÖLlische,” “DRAche” leaping out of the texture, and then even crazier melismatic festivity, with all sorts of interesting chromatic motion from the sopranos, followed by a da capo repeat of the first section. Upon completion of the first movement, I took the name of the Lord in vain, and started the whole thing over again, rather excited for my wife to return home from work so that I could play it for her. When I did, her eyes opened very wide, and we agreed that I’d have to start a campaign to perform the piece, which was last sung in Bethlehem in 1975. At long last, a few years after I first heard it, and nearly 40 years after that 1975 performance, here it is! We started working on those nearly insane melismas in September, and I’m happy to report that they’re ready to go.

The reason for the frenzy in the first movement is that it is a musical representation of the battle depicted in Dürer’s woodcut above. That is, St. Michael and his legion of angels are doing battle with the “raging serpent and the hellish dragon,” and Bach replies with incredibly vivid music. Buckle your seat belts, this is one extremely wild and hyperkinetic ride!

After an opening chorus of such frenzy and brilliance, you could be forgiven for thinking that what might follow are a few pedestrian recitatives and arias, along with a lovely final chorale, but Bach remains deeply inspired by the occasion and the texts for the day, which were Revelation 12:7-12, the source of the battle scene, and Matthew 18:1-11, in which Jesus exhorts his follows that unless they are like children, they shall not inherit the kingdom. Bach’s frequent collaborator, the poet Picander, supplied a text of great beauty. After a transitional recitative that transports us from the battle, we hear soprano aria for rustic oboes da caccia, in which the faithful are assured that God is present as a protector whether we “stay or move.” After another transitional recitative, there follows a tenor aria of exceptional beauty, in which the singer pleads for the angels to remain and to help him in his path, and “to sing your great salvation and to sing thanks to the Highest!” Over this plaintive aria, Bach superimposes another chorale melody, this time as an instrumental offering by the trumpet. Bach’s choice of the chorale is telling: it’s the tune with which he ends the St. John Passion, as well as another Michaelmas cantata, No. 149. He and Picander seem inspired by the Matthew’s gospel for the day and the image of a child-like faith, and listeners would know the text, “Let your dear little angel, at my final end, take my soul to Abraham’s bosom.” It’s a moment of striking beauty, and I can’t wait to hear Ben Butterfield, our fantastic tenor soloist, and Larry Wright, our wonderful principal trumpet, bring this movement to life. The final recitative, this time for soprano, is a prayer for the continued presence of angels, to help and guide us in this life, and to transport us to our heavenly reward. The final chorale pleads for the angels’ companionship on that journey, and for joy and comfort in heaven. Trumpets and timpani join in a festive harmonization of this chorale.

It’s been far too long since this challenging and exuberant cantata was last heard in Bethlehem, and I can’t wait for our audience to hear it. And, to hear it in context with the rest of the program, which will include Cantata 78, with its genius chaconne in the first movement, and the irresistible duet, “Wir eilen mich schwachen,” and then the conclusion of the program, Cantata 34, with it’s vivid depiction of the tongues of fire at Pentecost (as well as one of the most sublime arias in the Bach canon) makes this a can’t-miss program. Stay tuned, I’ll be writing about those, next!