The Narrator’s conclusion of W. H. Auden’s epic FOR THE TIME BEING: A Christmas Oratorio struck me as amusing when I read it recently, for several reasons, not least of which for the sort of inexorability that church musicians begin to feel early in the New Year:

The Christmas Feast is already a fading memory,

And already the mind begins to be vaguely aware

Of an unpleasant whiff of apprehension at the thought

Of Lent and Good Friday which cannot, after all, now

Be very far off.

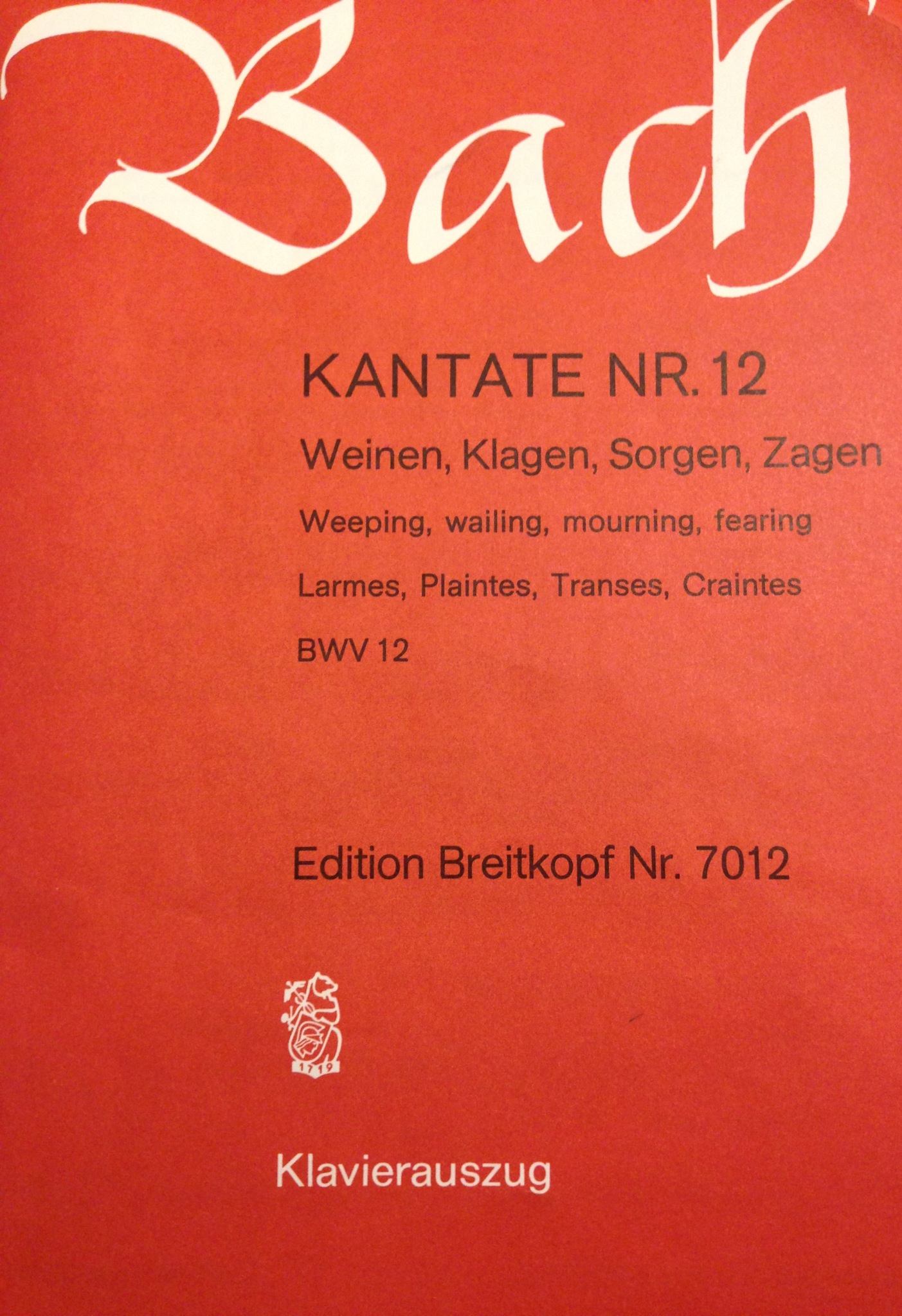

Lent is, indeed, right around the corner, and our performance on Tuesday will occur on the day before Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of Lent for Christians. Cantata 12 is an inspired choice, though it’s original provenance, composed during Bach’s time in Weimar, was actually intended for the third Sunday in the cycle following Easter. In the appointed gospel of that day (John 16:16-33), Jesus is in the midst of his Farewell Discourse, exhorting his disciples, “These things I have spoken unto you, that in me you might have peace. In the world you shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world.” Bach and his librettist respond with a cantata that paints, exquisitely, the movement from sorrow and tribulation to otherworldly joy.

Like Cantata 21, also thought to have been composed during Bach’s Weimar period, Cantata 12 begins with an achingly beautiful orchestral sinfonia, featuring a stunningly beautiful oboe obbligato (I also hear echoes of the sinfonia that begins Cantata 82, with sighing strings, and a gorgeous oboe obbligato). The Bach Festival Orchestra’s principal oboe, Mary Watt, will be playing the oboe obbligatos, and this cantata will feature her stellar artistry in several movements. Following the gorgeous Sinfonia is the opening chorus, which elevates the string’s sighs to new heights in the voices of the choir. Over a ground bass (or repeated pattern), each voice part of the choir enters in turn, with a sequence of words, “Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen,” each a word of inestimable sadness: “Weeping, Lamentation, Worry, Despair.” This small movement is one of Western music’s great laments, certainly equal to Purcell’s heartbreaking “When I Am Laid in Earth.” Each entrance is evocatively dissonant, with a deep sense of tension and release. This sense of lament is broken up, briefly by a more swiftly-moving B section, in three, in which torpor of the words from the beginning of the piece are held up as the “Christian’s bread of tears” which give us a kinship with the suffering of Jesus. After the B section resolves, the beginning is recapitulated, a plaintive echo of the beginning. The repetition of the bass line creates a powerful sense of resignation, almost a kind of trudging underneath the tension of the vocal lines, along with the almost metronomic quality of the upper strings. Such is the power of this music, that Bach later adapted it to become the Crucifixus in the Mass in B-Minor.

The Cantata continues with an accompanied recitative, sung by the alto, which reminds the listener that it is through tribulation that we enter the Kingdom of God. A halo of strings surround the singer with an extension of the tension and release of the opening chorus. Then follows an aria for alto, basso continuo, and oboe, in which the listener is reminded that “Cross and Crown” are inextricably interwoven, that “struggle and reward are united,” and that the Christian takes comfort in the wounds of Christ.

In this Cantata, Bach’s librettist Salomon Franck, and Bach, himself, seem to seek to capture the intimacy of Jesus’ words in the Farewell Discourse. In the next aria, for bass, the singer declaims, “I will follow Christ, I will not let him go,” a kind of echo of the anxiety of the disciples that is quelled by Jesus’ words of comfort and companionship. That declamation is rendered with no uncertain confidence by the soloist, who is also joined by an obbligato of duetting violins.

As if to underline the intimacy of the faithful and Jesus, a tenor aria follows, exhorting listeners to be faithful, “After the rain blessing blossoms, all storms pass away.” Over active counterpoint by the soloist and basso continuo, Bach quotes (again using the oboe) the chorale, Jesu, Meine Freude, “Jesu, my joy.” That chorale would certainly have been heard as rays of sun shining through the clouds to the congregation of Bach’s day. The melismatic melody of the tenor part seems to evoke more tribulation than comfort, but the oboe part crowns the whole affair with a penetrating beauty.

The Cantata concludes with the sturdy chorale, Was Gott tut, das ist wholgetan, “What God Does Is Well Done.” The instrumental ensemble is now crowned with an oboe descant (which will have Mary soaring high over everyone else, another image of heaven in music). In the text, we are reminded that sickness, death, and need are part of life, we will be enfolded in the “Fathers arms, evermore.”

In a sense, this Cantata seems to encapsulate the entire Christian journey through Lent and Easter in a scant seven movements. This evocative music takes us from unimaginable sadness to abiding faith and redemption, which is a musical journey that Bach seems to embark upon frequently in his oeuvre. What’s fascinating is the extraordinary diversity in how he explores that element of the Christian life in such varied ways, and from so many different angles. Next month, we’ll hear Dashon Burton sing Cantata 56, a solo baritone cantata that offers a similar journey of spiritual depth, but in a very different musical language (it will also feature some of Bach’s best melodies for the oboe), and in April, we’ll hear Bach’s stunning representation of Easter laughter, in his euphoric Cantata 31, Die Himmel Lacht, “The Heavens laugh.”

I am mindful that, in my role as the Bach Choir’s blogger, my work isn’t spiritual in nature, but it’s hard to resist donning a little bit of my other cap, as a professional church musician. This winter and spring, we’ll have the opportunity to take, in the form of the remaining three Bach at Noon concerts, a deeply-moving, soul-stirring spiritual journey, along side one of the great religious thinkers in history. Bach’s music, for those who would accept its blessings, unearths the very essence of the Christian faith (while also being some of the most aesthetically and intellectually satisfying music ever composed). Here is an opportunity to hear, in person, three distinct and powerful musical essays on the core mysteries of life. I don’t believe one necessarily needs to be a person of faith to experience the richness of this journey – viewed through just about any lens, be it spiritual, intellectual, musical, or otherwise, these performances will be deeply, deeply rewarding.

Speaking of deep rewards, Tuesday’s concert will overflow. Paired with the Cantata, Liz Field, our impeccable concertmaster, will be offering Bach’s Violin Partita in E. I could easily write another thousand words about this composition, which is for solo violin, alone. The performance of any of the partitas is an event, in and of itself, and I’m extremely excited to hear Liz’s take on this piece. Liz has a doctorate in historical performance from Cornell, but is not at all dogmatic about her approach to music-making. This will be a fusion of extraordinary performer and extraordinary music – Bach’s partitas are generally just one line of melody (with occasional double-stopping), but the melodies are so expertly crafted that they imply a universe of harmony – it would be hard to imagine anything else in the mix. In addition to the wonders of the musical craftsmanship, there’s a great deal of the intangible genius of those implied harmonies, which trick the listener’s mind into hearing more than what’s actually there. I hope you can join us (plan to arrive at 11:30, in order to get a good seat!).