The exact date on this cantata is unknown, though it likely came from Leipzig in the early 1730s (Melamed). Cantata 9 was written for the sixth Sunday after Trinity, and takes its text from the hymn of the same name by Paul Speratus. Each of the seven movements comes in some form from the hymn text, though only the first and last movements use the hymn text exactly. The interior movements all use an adapted text, rewritten by an unknown author.

The work is scored for SATB choir, SATB soloists, flute, oboe d’amore, strings, and continuo. The combination of the flute (transverse flute as opposed to recorder) with oboe d’amore at the very opening make for a sweet, gentle sound, though the gentle sound is juxtaposed with endless activity, almost in a perpetual motion manner. Melamed calls this first movement an “instrumental concerto featuring two solo woodwinds, with strings mostly in the role of the ripieno.” This virtuosity continues as a backdrop to the choir, which, in fact, adopts some of the sixteenth-note figurations (marked in blue) form the winds for its own. With the sopranos singing the chorale hymn tune (marked in red below) and the ATB voices ornamenting beneath, Bach weaves chorale fantasia and concerto together in a unique fashion in this first movement.

The middle movements alternate recitatives and arias, with all recitatives sung by the solo bass voice. Dürr suggest that using the same voice might suggest a kind of sermon is being presented in the recitatives. (Originally, the first recitative was written for alto solo, but Bach transposed it down for bass voice.) In fact, each of the recitatives refers to God’s law. Since Bach often associates the solo bass voice with the voice of God, might we interpret this vocal choice as Bach wanting to represent God Himself speaking to the people about how to follow his law?

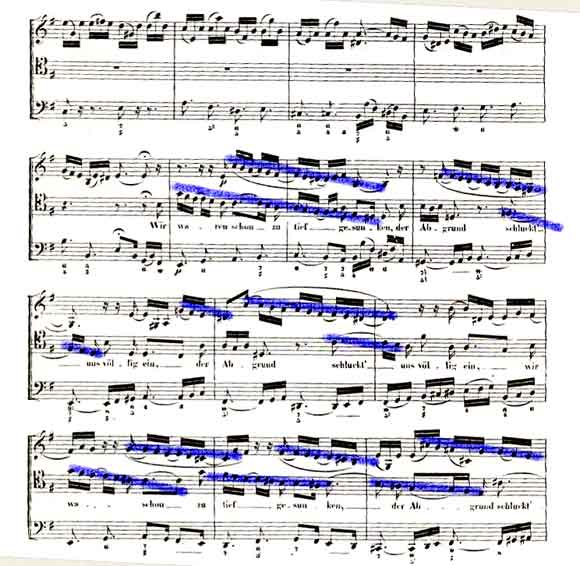

| Wir waren schon zu tief gesunken, Der Abgrund schluckt uns völlig ein, Die Tiefe drohte schon den Tod, Und dennoch kont in solcher Not Uns keine Hand behilfich sein. |

We were ere then too deeply fallen the chasm sucked us fully down, The deep then threatened us with death, And even still in such distress There was no hand to lend us help. |

|---|

You’ll also notice in the example below how often the vocal and instrumental lines descend (marked in blue), rather than ascend, lending further emphasis to the “deep” ideas in this text.

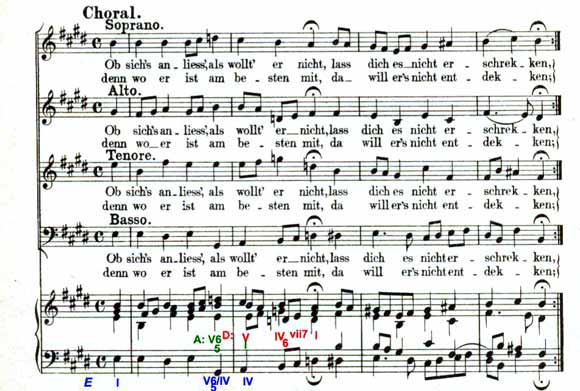

The next “aria” is actually a duet for solo soprano and solo alto, with obbligato woodwinds. Like the previous aria, this one is a da capo one, with the instrumental portion getting significant “air time.” (Officially, the tenor aria was a “dal segno aria”, because the pick-up note at the start of the score was not repeated, though it is written at the end of the music; the music thus returns to the sign (segno) which appears on the downbeat. The principle is the same as in a da capo aria.) The tone is distinctly different here than in the previous aria, where the sound is softened by the renewed appearance of the flute and oboe d’amore, but also by the return of a major key (A Major). The text would seem to indicate that man has again fallen short of God’s expectations and wishes in daily life, but the goodness of man’s heart can demonstrate our faith and essential goodness. Both the woodwind parts and the vocal parts employ imitation, in fact, sometimes exact imitation at the interval of a fifth, though the parts tend to cadence simultaneously, rather than continue the imitation. One might say that this represents different people on earth doing disparate activities, but coming together in faith.

The final chorale setting is in four parts in which the instruments of the orchestra double the SATB choral parts. While the scoring is unspectacular and expected, the harmonization is anything but. In particular, note Bach’s harmonic choices leading to the first cadence. As mentioned earlier, listeners expect a move to the subdominant (A Major), but in the first movement, Bach turns instead to F-sharp minor. This is not too wild as F-sharp minor is the relative minor of A Major, and thus a substitutable chord for students of music theory. But in the present example, Bach chooses instead to go to D Major (!), a far cry for the E Major in which the chorale begins. How does Bach pull this off? Common chord modulation: using a chord that belongs in both keys. Here the “pivot chord” is A Major, which serves three capacities: it is the subdominant chord (IV) in E Major, the key we start in; it is the tonic chord (I) in the key of A Major, which is the key we think we’re moving to; and it is the dominant chord (V) of D Major, the actual target key. Brilliant!