Although the text of this work is clearly sacred, the work was composed for annual civic celebrations in Mühlhausen. The work holds a special place among Bach’s total oeuvre for several reasons, including the following:

- It is one of the few works by Bach composed on commission, rather than those composed as part of his regular duties.

- It was published in Bach’s own lifetime, the only cantata by Bach to be so honored. (The city council, not the composer, paid for the publication of the work.)

- It is one of a small handful of Bach’s early works to survive in his own hand.

- It is the first work by Bach in which he employs a full festival orchestra. We see he is more than up to this task!

Bach himself referred to the work as a “Gratulatory Motetto”. This is probably not an indication of anything unusual in the work; rather, in late 17th century and the earliest years of the 18th century, the term “cantata” was generally reserved for solo secular vocal pieces in Italian. Sometimes, the terminology was as deliberately vague as “Music” vs. “Kirchenmüsik” (church music), never mind the interchangeability of terms such as cantata, motetto, actus, and concerto (modern audiences and musicologists would be intolerant of such lack of clarity!).

The work was written in 1708 and first performed in February 4 of that year. The text combines large portions of Psalm 74 with some hymn text and poetry. The largest portion, however, comes from the biblical source, and this is essentially the foundation for the entire work. According to Martin Petzolt:

Verses from Psalm 74 used in stanzas 1, 4, and 6 form the essential backbone for the overall text of BWV 71, moving along at three levels:

- God rules from ages past (movement 1: chorus)

- the old (both in age and in terms of office) mayor has the limits of his power laid down for him (movement 4: bass)

- the protection of the people is in God’s hand alone (movement 6: chorus)

These three levels are presented with a sense of doubt and consolidation (movements 2 and 3), acknowledgment of God’s power (movement 5), and good wishes (movement 7), which must have stirred the old – and at the time new [NOTE: the incumbent candidate was re-elected for a fifth term] – mayor in connection with his renewed assumption of office.

(See “Liturgical and Theological Aspects”, in The World of the Bach Cantatas: Johann Sebastian Bach’s Early Sacred Cantatas, Ed. Christoph Wolff [New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1995].)

The first movement is a sort of smörgåsbord of late Baroque style. In its mere 37 measures, Bach employs a full orchestra of three trumpets, timpani, two flutes, cello, two oboes, bassoon, two violins, viola, violone, and organ, along with SATB choir and SATB soloists. This large orchestra, especially with the trumpets and drums, allows a festive, brilliant mood to be set from the very start, but Bach never really allows the full orchestra and voices to sound together for too long, nor does either the texture or timbre remain a constant for any stretch. The choral parts are almost exclusively homophonic and accompanied by the full orchestra, with active sixteenth-note passages providing transitions between choral outbursts; meanwhile, the solo voices are polyphonic and accompanied by strings and continuo. The music is set primarily in C major, but quick side trips to a minor and d minor provide a modicum of tonal variety.

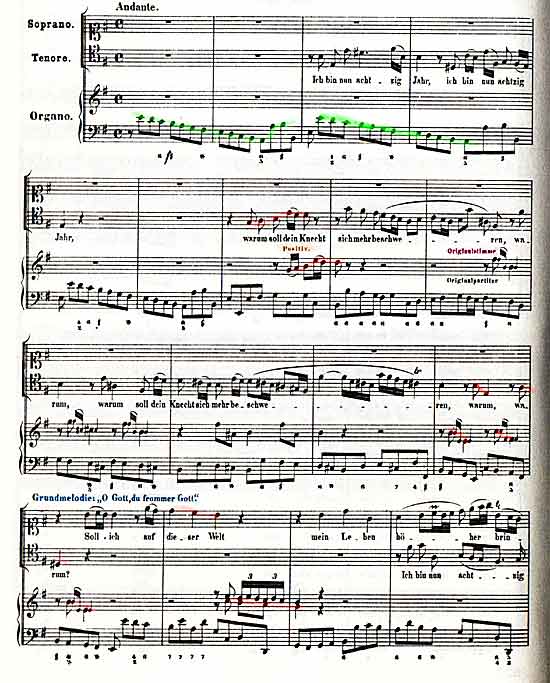

In 1708, when the work was written, Bach’s primary job was as the organist at St. Blasius’s church in Mühlhausen. It is therefore no surprise that: 1. Bach did not write many compositions in this time, and 2. that when he did, the organ is given a more important role than was typical at that time. A good example of his special treatment of the organ occurs in the second movement, “Ich bin nun achtzig Jahr”, of Cantata 71, an aria for soprano and tenor with organ alone – there are no other supporting instruments. Initially, the organ “merely” provides continuo-type support, but by the seventh measure, the organ takes on an independent role, echoing the vocal lines; Bach indicates that these echoing passages are to be played in the “Positiv”, where the pipes were normally physically separated from the other divisions of the organ, enhancing the echo effect through distance.

What you see in the score excerpt below are the following items:

- In green, a sample of the more traditional continuo-style writing for the organ; in this case, the continuo writing extends beyond the green marked in the score. The bass line throughout is a walking bass line, typical of the high Baroque era.

- In orange, note Bach’s instruction “positiv”, indicating that this brief passage should be played on the Positiv (or Rückpositiv) of the organ.

- In pink, Bach’s instruction “Originalstimme”, or original voice, meaning the organist should switch to whatever he/she had used as the original voicing in this movement.

- In red, the echoing passages between the organ and voices.

- In blue, the marking “Grundmelodie: ‘O Gott, du frommer Gott'”. This is an indication that Bach is employing a chorale melody here. The movement is marked “Aria con Chorale in Canto”. Indeed, the chorale melody is inserted into the solo soprano line, but it is heavily ornamented – were it not for the occasional quarter notes (which stand out as very long in this andante movement) and Bach’s score indications, listeners might miss the chorale tune altogether.

Eventually, the organ’s role in this movement evolves even further into an elaborate featured solo passage to close the movement.

In movement three we find the first of two fugues in this cantata. Here, the “coro senza ripieni” (chorus without tutti) presents a four-voice fugue. It is set in a minor, relative minor to the primary key of the first movement, and one position away on the circle of fifths from the preceding movement, set in e minor. One might think that with the C major – e minor – a minor key arrangement of the first three movements, a return to C is in the works for movement four. Such is not the case. In fact, Bach moves to “the flat side” for the bass arioso which follows. The depth of the bass voice is offset by the higher and lighter sounds of two oboes and two flutes. Konrad Küster, professor of musicology at Freiburg University, writes that this movement is not a da capo aria, but rather a series of short refrains in an A-B-A arrangement. It is, indeed, composed of two contrasting sections. The two sections are outlined below:

| Part I | Part II |

| F Major | F Major, g minor, B-Flat major, d minor, F Major |

| 3/2 | 4/4 |

| Lento | No tempo marking, but much more rhythmic activity |

| Primarily half notes and quarters throughout the texture | Eighth to sixteenths are predominant |

| “Tag und Nacht is dein” (Day and night are yours) | “Du machest, dass beide, Sonn und Gestirn, ihren gewissen lauf haben. Du setzest einem jeglichen Lande seine Granze” (You make the sun, the moon and the stars, as you bid them, to run duly. For every country here on the earth, you have set the borders.) |

| 22 measures | 18 measures |

| 2 flutes, 2 oboes, cello, bassoon, organ | Organ |

The second section is not entirely self-contained, as the cadence from V to I in F major provides the bridge back to the music of the opening. Despite Küster’s claim that this is not a da capo aria, I doubt modern audiences would perceive it any other way.

One last note on this movement: Bach’s use of word painting is amusing here. Each time the bass soloists sings the word “Nacht” (night), the vocal line makes a gap. In this way, night remains distinct from day, with the day (“Tag”) always being higher and brighter and the night always falling.

In the final movement, Bach employs a “permutation fugue”. The permutation fugue was a common feature in keyboard works of the day. It is “so named because the voices enter in canon-like fashion, with two or three counter subjects appearing after the main theme, as beads on a string, in each voice. After the initial exposition, the order of entries can be altered, and the entire structure can be transposed to another key, in order to produce different permutations of the original material” (George B. Stauffer, “Bach the organist”, 90, in The World of the Bach Cantatas, ed. Christoph Wolff [New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1995]). Many of Bach’s earlier works were indeed for keyboard, and we already know that he was a master of fugal writing. It is no surprise that, given his limited experience in writing choral works at this time in his career, Bach would turn to the more comfortable world of keyboard music to find some inspiration. The fugue only lasts 45 measures (followed by a three-measure closing by the orchestra alone, as a transition to the final section of this movement).

The fugue is marked “senza ripieni”, meaning the orchestra drops out, except, of course, the continuo line. “Ripieni” is an alternate term for “tutti”, meaning all or everyone. The term is most common in works of the concerto grosso genre, of which this piece is not an example. However, the underlying principle driving the concerto grosso is the juxtaposition of two ensembles, one larger (ripieno) and one smaller (concertino). This combination of different ensembles allows for a variety of textural, dynamic, and timbral possibilities. Bach creates such variety here by omitting the ripieno (orchestra) and allowing a primarily vocal sound to dominate the opening of the fugue. Gradually, after each of the voices in the choir (in SATB order) has entered with the fugue subject, the same subject spreads into the orchestra. The orchestra follows the order established by the voices in having the subject introduced first by instruments in the highest register, then the alto, tenor, and bass registers respectively. Once the fugue has built to include all instruments but trumpets and drums they, too, enter to bring the fugue to a climax, providing affirming punctuations before a cadence brings the fugue to a close. The movement does not yet end, however, until an additional choral section, featuring primarily chordal entrances and a flurry of descending scale passages in the orchestra to conclude the movement with an insistent shout of “Glück, Heil, Glück, Heil und grosser Sieg!” to both God and the new mayor.

The work made such a good impression that the council asked Bach to write another festival work for the following year; by the time a year had passed, however, Bach had moved on to Weimar.