Cantata 182 is a cantata for Palm Sunday or the feast of the Annunciation. Because of its associate with Palm Sunday, it is often considered an Easter cantata. It is certainly more festive than most Lenten cantatas, and Palm Sunday is a day of celebration, as Christ triumphantly enters the city of Jerusalem to shouts of “Hosanna”. The cantata was written for the Duke of Weimar shortly after Bach’s appointment there as Konzertmeister, and premiered on March 25, 1714, marking the beginning of a monthly Weimar cantata cycle (Christoph Wolff). The work was subsequently revived by Bach for performances in 1724 and 1728, and perhaps other times as well. In each revival, Bach added to the instrumentation.

The librettist is not known, but Salomo Franck, who was a Weimar court poet and who wrote other texts for Bach, is frequently cited as the author. The text is based on Psalm 40 and uses a text from Stockmann’s 1633 chorale, “Jesu Leiden, Pein und Tod”. This is a particularly appropriate text for anticipating what will happen later in Holy Week, after the glorious sounds of Christ’s entrance to Jerusalem have faded:

| Jesu, deine Passion Ist mir lauter Freude, Deine Wunden, Kron, und Hohn Meines Herzens Weide. Meine Seel auf Rosen geht, Wenn ich dran gedenke, In dem Himmel eine Stätt Mir deswegen schenke! |

Jesus, Your passion is pure joy to me, Your wounds, thorns and shame my heart’s pasture; my soul walks on roses when I think upon it; grant me a place in heaven for me for its sake |

The cantata is set in seven movements, beginning with a “sonata” – indicating that the first movement was intended for instruments only. It is typical of Bach’s early cantatas to begin with an independent instrumental prelude (Christoph Wolff, The World of the Bach Cantatas [New York: W.W. Norton, 1997], 150). In this case, the full orchestra (here, recorder or flute with strings and continuo) is separated into groups: strings and continuo together as an accompaniment, playing chords on each beat, while a solo violin and the flute/recorder soloist trade rising dotted-figure lines. One wonders if the dotted figures, so often associated with majesty, somehow symbolize Christ in his majesty riding into Jerusalem?

The second movement is a da capo chorus, beginning with a fugal exposition that ultimately gives way to a homophonic texture. The “b” section features imitative entrances in very close proximity (only one beat apart) – only a true contrapuntal master could pull this off.

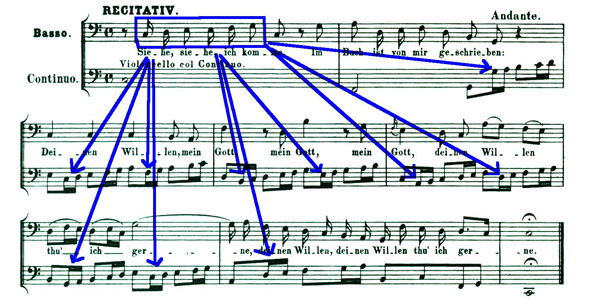

A brief simple recitative follows, in which the continuo repeats ten times what the vocal bass soloist sings in the first phrase.

Here follows three consecutive arias, one each for solo bass, alto, and tenor, respectively; each vocal soloist is accompanied by an active obbligato instrumental part (violin, flute, and continuo, respectively). Moving from the first to the third, the texture thins: the bass is accompanied by unison violins plus a solo violin and continuo (three separate instrumental parts); the alto is accompanied by solo flute plus continuo (two separate instrumental parts); and the tenor by continuo alone (one instrumental part). It’s not clear that this gradual reduction in texture has any symbolic meaning, but it is certain to provide a wide variety of sounds for the listeners.

Of the bass aria, Alec Robertson (in The Church Cantatas of J.S. Bach) writes, “The music, though dignified, is oddly neutral and does not reflect the lofty sentiment of the text.” Before considering this statement, we need, of course, to review the text:

| Starkes Lieben, das dich, grosser Gottessohn, von dem Thron deiner Herrlichkeit getrieben, dass du dich zum Heil der Welt als ein Opfer fürgestellt, dass du dich mit Blut verschrieben. |

Strong love, great Son of God, that drove you from your throne of glory, so that you, for the salvation of the world, were presented as as a sacrifice, as you pledged in writing by your blood. |

To be honest, I’m not certain what Robertson wants. Is it that the music should sound more glorious? Should it be darker, given that the Son of God was driven from the glorious throne to be sacrificed? Perhaps more twisted harmonies on “Blut” would be more appropriate.

No. I find “neutral” a curious word choice. This gentle, lilting anthem emphasized, in my mind, the strong love of Christ. In Bach’s setting, I see more a reflection of the famous quote from I Corinthians 13:4-7:

Love is patient and kind. Love is not jealous or boastful or proud or rude. Love does not demand its own way. Love is not irritable and it keeps no record of when it has been wronged. It is never glad about injustice but rejoices whenever the truth wins out. Love never gives up, never loses faith, is always hopeful, and endures through every circumstance.

The music is not boastful or proud. It is not demanding, nor irritable. It is hopeful, yes, indeed; and the continuing movement gives it an enduring feeling. It is constant, faithful, assured, calm…hardly “neutral”, for love can never be neutral.

The last of the three arias will undoubtedly get some notice from listeners, because it is so different from the previous two. As stated above, it is performed by solo tenor voice and continuo alone. While providing a textural contrast to the previous two arias, “Jesu, lass durch Wohl und Weh” presents a subtle variety of textures within this movement alone. Do not allow the continuous sound of tenor voice and continuo distract you from the changes in activity, between running sixteenth notes in the continuo and passages where the tenor and continuo are in rhythmic unison (eighth notes). Most notable are the five moments within where there is a rest in both parts. The sudden stoppage of motion and sound is striking in each case.

The next (7th) movement is a chorale fantasy containing a fugue. The text for this movement comes from Stockmann’s 1633 chorale, “Jesu Leiden, Pein und Tod”. The chorale tune, unadorned, appears in the chorale soprano line doubled by the flute and solo violin.

The eighth and final movement is another fugue, in this case, a permutation fugue. This type of fugue occurs most often in early cantatas of Bach, including movements from Cantatas 71, 131, and 21, and is Bach’s own invention. A permutation fugue is adapted from keyboard style, and occurs when “voices enter in canon-like fashion, with two or three counter subjects appearing after the main theme, as beads on a string, in each voice. After the initial exposition, the order of entries can be altered, and the entire structure…transposed to another key, in order to produce different permutations of the original material” (Christoph Wolff, The World of the Bach Cantatas [New York: W.W. Norton, 1997], 90).